Editor’s Note: This blogpost is a repost of the original content published on 5 March 2024, by Bidhan Roy and Marcos Villagra from Bagel. Founded in 2023 by CEO Bidhan Roy, Bagel is a machine learning and cryptography research lab building a permissionless, privacy-preserving machine learning ecosystem. This blogpost represents the independent view of these authors, whom have given their permission for this re-publication.

Trillion-dollar industries are unable to leverage their immensely valuable data for AI training and inference due to privacy concerns. The potential for AI-driven breakthroughs—genomic secrets that could cure diseases, predictive insights to eliminate supply chain waste, and chevrons of untapped energy sources—remain locked away. Privacy regulations also closely guard this valuable and sensitive information.

To propel human civilization forward in energy, healthcare, and collaboration, it is crucial to enable AI systems that train and generate inference on data while maintaining full end-to-end privacy. At Bagel, pioneering this capability is our mission. We believe accessing a fundamental resource like knowledge, for both human-driven and autonomous AI, should not entail a compromise on privacy.

We have applied and experimented with almost all the major privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML) mechanisms. Below, we share our insights, our approach, and some research breakthroughs.

And if you’re in a rush, we have a TLDR at the end.

Privacy-preserving Machine Learning (PPML)

Recent advances in academia and industry have focused on incorporating privacy mechanisms into machine learning models, highlighting a significant move towards privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML). At Bagel, we have experimented with all the major PPML techniques, particularly those post differential privacy. Our work, positioned at the intersection of AI and cryptography, draws from the cutting edge in both domains.

Our research covered a wide range of PPML techniques suitable for our platform. Among those, Differential Privacy (DP), Federated Learning, Zero-knowledge Machine Learning (ZKML) and Fully Homomorphic Encryption Machine Learning (FHEML) stood out for their potential in PPML.

First, we will delve into each of these, examining their advantages and drawbacks. In subsequent posts, we will describe Bagel’s approach to data privacy, which addresses and resolves the challenges associated with the existing solutions.

Differential Privacy (DP)

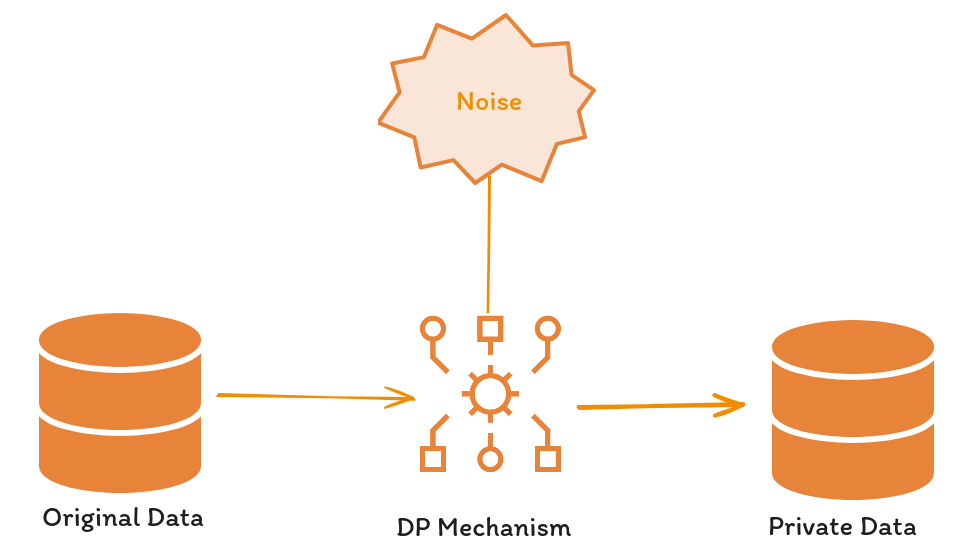

One of the first and most important techniques with a mathematical guarantee for incorporating privacy into data is differential privacy or DP (Dwork et al. 2006), addressing the challenges faced by earlier methods with a quantifiable privacy definition.

DP ensures that a randomized algorithm, A, maintains privacy across datasets D1 and D2—which differ by a single record—by keeping the probability of A(D1) and A(D2) generating identical outcomes relatively unchanged. This principle implies that minor dataset modifications do not significantly alter outcome probabilities, marking a pivotal advancement in data privacy.

The application of DP in machine learning, particularly in neural network training and inference, demonstrates its versatility and effectiveness. Notable implementations include adapting DP for supervised learning algorithms by integrating random noise at various phases: directly onto the data, within the training process, or during inference, as highlighted by Ponomareva et al. (2023) and further references.

The balance between privacy and accuracy in DP is influenced by the noise level: greater noise enhances privacy at the cost of accuracy, affecting both inference and training stages. This relationship was explored by Abadi et al. in (2016) through the introduction of Gaussian noise to the stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD) algorithm, observing the noise’s impact on accuracy across the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets.

An innovative DP application, Private Aggregation of Teacher Ensembles (PATE) by Papernot et al. in (2016), divides a dataset into disjoint subsets, training networks on each without privacy, termed as teachers. These networks’ aggregated inferences, subjected to added noise for privacy, inform the training of a student model to emulate the teacher ensemble. This method also underscores the trade-off between privacy enhancement through noise addition and the resultant accuracy reduction.

Further studies affirm that while privacy can be secured with little impact on execution times (Li et a. 2015), stringent privacy measures can obscure discernible patterns essential for learning (Abadi et al. 2016). Consequently, a certain level of privacy must be relinquished in DP to facilitate effective machine learning model training, illustrating the nuanced balance between privacy preservation and learning efficiency.

Pros of Differential Privacy

The advantages of using DP are:

Effortless. Easy to implement into algorithms and code.

Algorithm independence. Schemes can be made independent of the training or inference algorithm.

Fast. Some DP mechanisms have shown to have little impact on the execution times of algorithms.

Tunable privacy. The degree of desired privacy can be chosen by the algorithm designer.

Cons of Differential Privacy

Access to private data is still necessary. Teachers in the PATE scheme must have full access to the private data (Papernot et al. 2016) in order to train a neural network. Also, the stochastic gradient descent algorithm based on DP only adds noise to the weight updates and needs access to private data for training (Abadi et al. 2016).

Privacy-Accuracy-Speed trade-off on data. All implementations must sacrifice some privacy in order to get good results. If there is no discernable pattern in the input, then there is nothing to train (Feyisetan et al. 2020). The implementation of some noise mechanisms can impact execution times, necessitating a balance between speed and the goals of privacy and accuracy.

Zero-Knowledge Machine Learning (ZKML)

A zero-knowledge proof system (ZKP) is a method allowing a prover P to convince a verifier V about the truth of a statement without disclosing any information apart from the statement’s veracity. To affirm the statement’s truth, P produces a proof π for V to review, enabling V to be convinced of the statement’s truthfulness.

Zero-Knowledge Machine Learning (ZKML) is an approach that combines the principles of zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) with machine learning. This integration allows machine learning models to be trained and to infer with verifiability.

For an in-depth examination of ZKML, refer to the work by Xin et al. in (2023). Below we provide a brief explanation that focuses on the utilization of ZKPs for neural network training and inference.

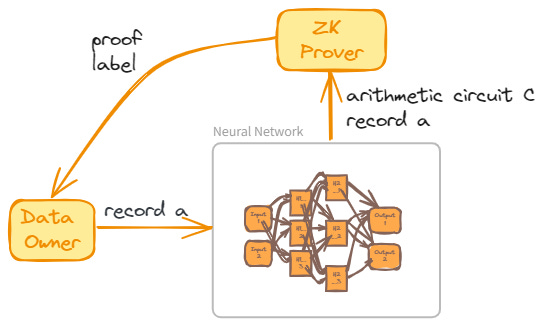

ZKML Inference

Consider an unlabeled dataset A and a pretrained neural network N tasked with labeling each record in A. To generate a ZK proof of N‘s computation during labeling, an arithmetic circuit C representing N is required, including circuits for each neuron’s activation function. Assuming such a circuit C exists and is publicly accessible, the network’s weights and a dataset record become the private and public inputs, respectively. For any record a of A, N‘s output is denoted by a pair (l,π), where l is the label and π is a zero-knowledge argument asserting the existence of specific weights that facilitated the labeling.

This model illustrates how ZK proves the accurate execution of a neural network on data, concealing the network’s weights within a ZK proof. Consequently, any verifier can be assured that the executing agent possesses the necessary weights.

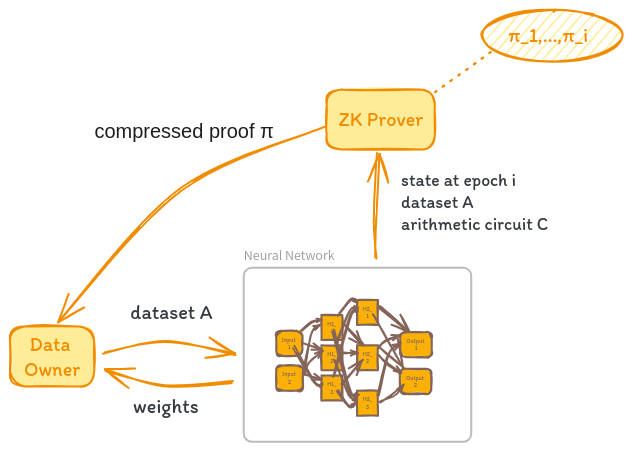

ZKML Training

ZKPs are applicable during training to validate N‘s correct execution on a labeled dataset A. Here, A serves as the public input, with an arithmetic circuit C depicting the neural network N. The training process requires an additional arithmetic circuit to implement the optimization function, minimizing the loss function. For each training epoch i, a proof π_i is generated, confirming the algorithm’s accurate execution through epochs 1 to i-1, including the validity of the preceding epoch’s proof. The training culminates with a compressed proof π, proving the correct training over dataset A.

The explanation above illustrates that during training, the network’s weights are concealed to ensure that the training is correctly executed on the given dataset A. Additionally, all internal states of the network remain undisclosed throughout the training process.

Pros of ZKML

The advantages of using ZKPs with neural networks are:

Privacy of model weights. The weights of the neural network are never revealed during training or inference in any way. The weights and the internal states of the network algorithm are private inputs for the ZKP.

Verifiability. The proof certifies the proper execution of training or inference processes and guarantees the accurate computation of weights.

Trustlessness. The proof and its verification properties ensure that the data owner is not required to place trust in the agent operating the neural network. Instead, the data owner can rely on the proof to confirm the accuracy of both the computation and the existence of correct weights.

Cons of ZKML

The disadvantages of using ZKPs with neural networks are:

No data privacy. The agent running the neural network needs access to the data in order to train or do inference. Data is considered a parameter that is publicly known to the data owner and the prover running the neural network (Xing et al. 2023).

No privacy for the model’s algorithm. In order to create a ZK proof, the algorithm of the entire neural network should be publicly known. This includes the activation functions, the loss function, optimization algorithm used, etc (Xing et al. 2023).

Proof generation of an expensive computation. Presently, the process of generating a ZK proof is computationally demanding—-see for example this report on the computation times of ZK provers. Creating a proof for each epoch within a training algorithm can exacerbate the computational burden of an already resource-intensive task.

Federated Learning (FL)

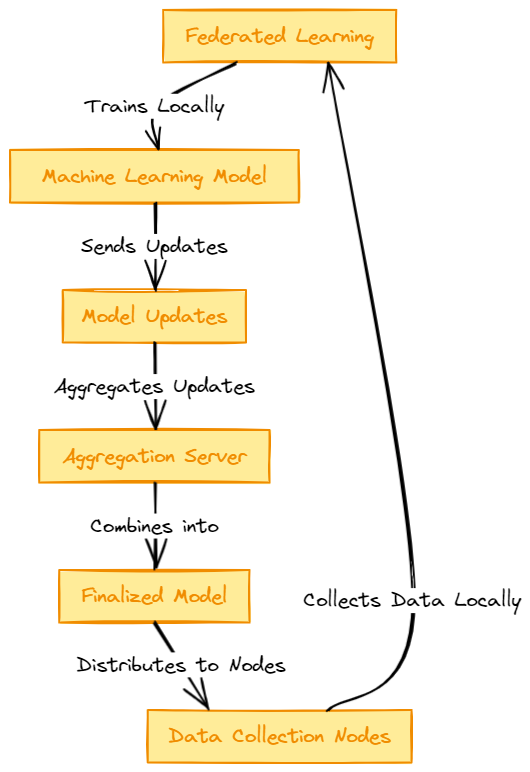

In Federated Learning or FL we look to train a global model using a dataset that is distributed in multiple servers with local data samples but without each server sharing their local data.

In FL there is a global objective function that is being optimized which is defined as

𝑓(𝑥1,…,𝑥𝑛)=1𝑛∑𝑖=1𝑛𝑓𝑖(𝑥𝑖),\(f(x_1,\dots,x_n)=\frac 1 n \sum_{i=1}^n f_i(x_i),\)

where n is the number of servers, each variables is the set of parameter as viewed by the server i, and each function is a local objective function of server i. FL tries to find the best set of values that optimizes f.

The figure below shows the general process in FL.

- Initialization. An initial global model is created and distributed by a central server to all other servers.

- Local training. Each server trains the model using their local data. This ensures data privacy and security.

- Model update. After training, each server shares with the central server their local updates like gradients and parameters.

- Aggregation. The central server receives all local updates and aggregates them into the global model, for example, using averaging.

- Model distribution. The updated model is distributed again with local servers and the previous steps are repeated until a desired level of performance is achieve by the global model.

Since local servers never share their local data, FL guarantees privacy over that data. However, the model being constructed is shared among all parties, and hence, its structure and set of parameters are not hidden.

Pros of FL

The advantages of using FL are:

Data privacy. The local data on the local servers are never shared. All computations are done locally, and there is no need of communication between them.

Distributed computing. The creation of the global model is distributed among local servers, thereby parallelizing a resource-intensive computation. Thus, FL is considered a distributed machine learning framework (Xu et al. 2021).

Cons of FL

The disadvantages of using FL are:

Model is not private. The global model is shared among each local server in order to do their computations locally. This includes the aggregated weights and gradients at each step of the FL process. Thus, each local server is aware of the entire architecture of the global model (Konečný et al. 2016).

Data leakage. Recent research indicates that data leakage remains a persistent issue, notably through mechanisms such as gradient sharing—see for example Jin et al. (2022). Consequently, FL cannot provide complete assurances of data privacy.

Trust. Since no proofs are generated in FL, every party involved in the process need to be trusted that their computation and parameters were computed as expected (Gao et al. 2023).

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE)

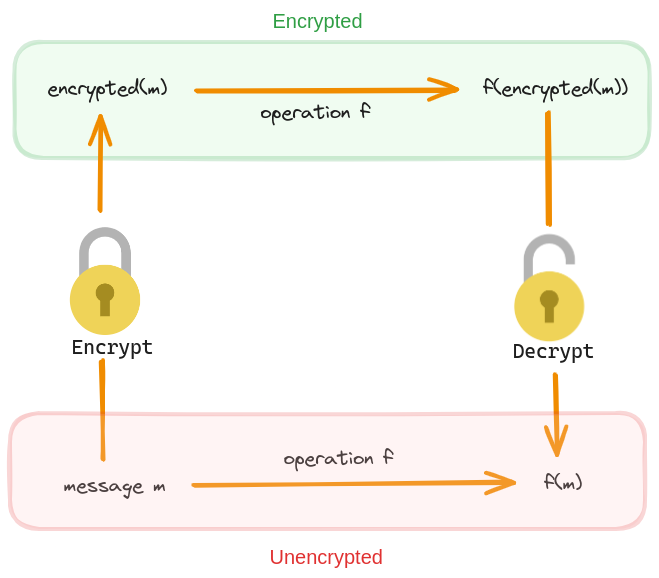

At its core, homomorphic encryption permits computations on encrypted data. By “homomorphic,” we refer to the capacity of an encryption scheme to allow specific operations on ciphertexts that, when decrypted, yield the same result as operations performed directly on the plaintexts.

Consider a scenario with a secret key k and a plaintext m. In an encryption scheme (E,D), where E and D represent encryption and decryption algorithms respectively, the condition D(k,E(k,m))=m must hold. A scheme (E,D) is deemed fully homomorphic if for any key k and messages m, the properties E(k,m+m’)=E(k,m)+E(k,m’) and E(k,m*m’)=E(k,m)* E(k,m’) are satisfied, with addition and multiplication defined over a finite field. If only one operation is supported, the scheme is partially homomorphic. This definition implies that operations on encrypted data mirror those on plaintext, crucial for maintaining data privacy during processing.

In plain words, if we have a fully homomorphic encryption scheme, then operating over the encrypted data is equivalent to operating over the plaintext. We will write FHE to refer to a fully homomorphic encryption scheme. The figure below shows how an arbitrary homomorphic operation works over a plaintext and ciphertext.

The homomorphic property of FHE makes it invaluable in situations where data must remain secure while still being used for computations. For instance, if we possess sensitive data and require a third party to perform data analysis on it, we can rely on FHE to encrypt the data. This allows the third party to conduct analysis on the encrypted data without the need for decryption. The mathematical properties of FHE guarantee the accuracy of the analysis results.

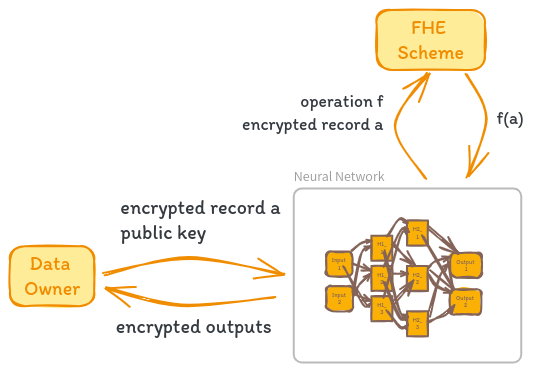

FHE Inference

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) can be used to perform inference in neural networks while preserving data privacy. Let’s consider a scenario where N is a pretrained neural network, A is a dataset, and (E,D) is an asymmetric FHE scheme. The goal is to perform inference on a record a of A without revealing the sensitive information contained in a to the neural network.

The inference process using FHE begins with encryption. The data owner encrypts the record a using the encryption algorithm E with the public key public_key, obtaining the encrypted record a’ = E(public_key, a).

Next, the data owner sends the encrypted record a’ along with public_key to the neural network N. The neural network N must have knowledge of the encryption scheme (E,D) and its parameters to correctly apply homomorphic operations over the encrypted data a’. Any arithmetic operation performed by N can be safely applied to a’ due to the homomorphic properties of the encryption scheme.

One challenge in using FHE for neural network inference is handling non-linear activation functions, such as sigmoid and ReLU, which involve non-arithmetic computations. To compute these functions homomorphically, they need to be approximated by low-degree polynomials. The approximations allow the activation functions to be computed using homomorphic operations on the encrypted data a’.

After applying the necessary homomorphic operations and approximated activation functions, the neural network N obtains the inference result. It’s important to note that the inference result is still in encrypted form, as all computations were performed on encrypted data.

Finally, the encrypted inference result is sent back to the data owner, who uses the private key associated with the FHE scheme to decrypt the result using the decryption algorithm D. The decrypted inference result is obtained, which can be interpreted and utilized by the data owner.

By following this inference process, the neural network N can perform computations on the encrypted data a’ without having access to the original sensitive information. The FHE scheme ensures that the data remains encrypted throughout the inference process, and only the data owner with the private key can decrypt the final result.

It’s important to note that the neural network N must be designed and trained to work with the specific FHE scheme and its parameters. Additionally, the approximation of non-linear activation functions by low-degree polynomials may introduce some level of approximation error, which should be considered and evaluated based on the specific application and accuracy requirements.

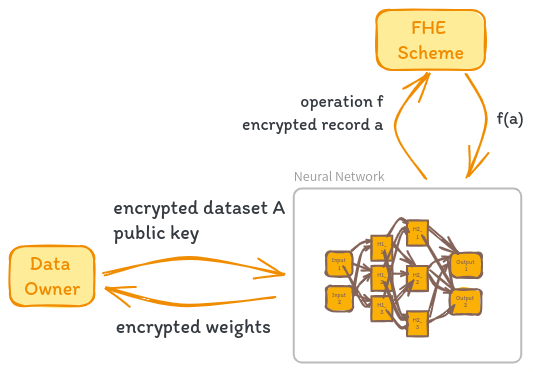

FHE Training

The process of training a neural network using Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) is conceptually similar to performing inference, but with a few key differences. Let’s dive into the details.

Imagine we have an untrained neural network N and an encrypted dataset A’ = E(public_key, A), where E is the encryption function and public_key is the public key of an asymmetric FHE scheme. Our goal is to train N on the encrypted data A’ while preserving the privacy of the original dataset A.

The training process unfolds as follows. Each operation performed by the network and the training algorithm is executed on each encrypted record a’ of A'. This includes both the forward and backward passes of the network. As with inference, any non-arithmetic operations like activation functions need to be approximated using low-degree polynomials to be compatible with the homomorphic properties of FHE.

A fascinating aspect of this approach is that the weights obtained during training are themselves encrypted. They can only be decrypted using the private key of the FHE scheme, which is held exclusively by the data owner. This means that even the agent executing the neural network training never has access to the actual weight values, only their encrypted counterparts.

Think about the implications of this. The data owner can outsource the computational heavy lifting of training to a third party, like a cloud provider with powerful GPUs, without ever revealing their sensitive data. The training process operates on encrypted data and produces encrypted weights, ensuring end-to-end privacy.

Once training is complete, the neural network sends the collection of encrypted weights w’ back to the data owner. The data owner can then decrypt the weights using his private key, obtaining the final trained model. He is the sole party capable of accessing the unencrypted weights and using the model for inference on plaintext data.

There are a few caveats to keep in mind. FHE operations are computationally expensive, so training a neural network with FHE will generally be slower than training on unencrypted data.

Pros of FHE

The advantages of using FHE are:

Data privacy. Third-party access to encrypted private data is effectively prevented, a security guarantee upheld by the assurances of FHE and lattice-based cryptography (Gentry 2009).

Model privacy. Training and inference processes are carried out on encrypted data, eliminating the need to share or publicize the neural network’s parameters for accurate data analysis.

Effectiveness. Previous studies have demonstrated that neural networks operating on encrypted data using FHE maintain their accuracy—see for example Nandakumar et al. (2019) and Xu et al. (2019). Therefore, we can be assured that employing FHE for training and inference processes will achieve the anticipated outcomes.

Quantum resistance. The security of FHE, unlike other encryption schemes, is grounded in difficult problems derived from Lattice theory. These problems are considered to be hard even for quantum computers (Regev 2005), thus offering enhanced protection against potential quantum threats in the future.

Cons of FHE

The disadvantages of using FHE are:

Verifiability. FHE does not offer proofs of correct encryption nor correct computation. Hence, we must rely on trust that the data intended for encryption is indeed the correct data (Viand et al. 2023).

Speed. Relative to conventional encryption schemes, FHE is still considered to be slow during parameter setups, encryption and decryption algorithms (Gorantala et al. 2023).

Memory requirements. The number of weights that need to be encrypted are proportional to the size of the network. Even for small networks, the RAM memory requirements are in the order of gigabytes (Chen et al. 2018), (Nandakumar et al. 2019).

Usability. FHE schemes use many parameters that need to be carefully tuned and requires extensive experience from users (Al Badawi et al. 2022), (Halevi & Shoup 2020).

TLDR

We examined the four most widely used privacy-preserving techniques in machine learning, focusing on neural network training and inference. We evaluated these techniques across four dimensions: data privacy, model algorithm privacy, model weights privacy, and verifiability.

Data privacy considers the model owner’s access to private data. Differential privacy (DP) and zero-knowledge machine learning (ZKML) require access to private data for training and proof generation, respectively. Federated learning (FL) enables training and inference without revealing data, while fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) allows computations on encrypted data.

Model algorithm privacy refers to the data owner’s access to the model’s algorithms. DP does not require algorithm disclosure, while ZKML necessitates it for proof generation. FL distributes algorithms among local servers, and FHE operates without accessing the model’s algorithms.

Model weights privacy concerns the data owner’s access to the model’s weights. DP and ZKML keep weights undisclosed or provide proofs of existence without revealing values. FL involves exchanging weights among servers for decentralized learning, contrasting with DP and ZKML’s privacy-preserving mechanisms. FHE enables training and inference on encrypted data, eliminating the need for model owners to know the weights.

Verifiability refers to the inherent capabilities for verifiable computation. ZKML inherently provides this capability. DP, FL, and FHE would not provide similar levels of integrity assurance.

The table below summarizes our findings:

What’s Next 🥯

At Bagel, we recognize that existing privacy-preserving machine learning solutions fall short in providing end-to-end privacy, scalability, and strong trust assumptions. To address these limitations, our team has developed a novel approach based on a modified version of homomorphic encryption (FHE).

Our pilot results are extremely promising, indicating that our solution has the potential to revolutionize the field of privacy-preserving machine learning. By leveraging the strengths of homomorphic encryption and optimizing its performance, we aim to deliver a scalable, trustworthy, and truly private machine learning framework.

We believe that our work represents a paradigm shift in the way machine learning is conducted, ensuring that the benefits of AI can be harnessed without compromising user privacy or data security. As we continue to share more about our approach, we invite you to follow our progress by subscribing to the Bagel blog.

For more thought pieces from Bagel, follow out their blog here.

To stay updated on the latest Filecoin happenings, follow the @Filecointldr handle.

Disclaimer: This information is for informational purposes only and is not intended to constitute investment, financial, legal, or other advice. This information is not an endorsement, offer, or recommendation to use any particular service, product, or application.